Recently I read an article dating back to 2014 where novelist and journalist Will Self posed the question “is the novel dead?” The inference being that literary works, unlike genre specific fiction, had not transitioned well into the age of digital media. Throughout the article, Self makes several valid and interesting points, especially when chronicling the rise of the classic novel and exploring the possible link between “serious writing,” such as James Joyce’s Ulysses and class divides that may see sections of society alienated from a type of writing that does not reflect their existential outlook. Self also explored the role of book sales in relation to genres that agents and publishers may perceive as more financially viable than highbrow literary novels that often lack mass appeal. The idea that literary fiction may have regressed due to a cultural shift accentuated by technological advances interested me from the perspective of both a book enthusiast and a writer who has struggled with the meaning of genre as it relates to my work. Whilst I’d previously placed my writing securely in the literary fiction category, I was forced into deep contemplation when a published author, charged with critiquing a sample of my work, casually commented that in market terms my novel would be considered commercial. Commercial? What did that mean? I couldn’t help but assume that he viewed my book as easily digestible, like Fifty Shades of Grey, and whilst I would have welcomed the millions associated with the highly successful novel, I also valued my artistic integrity. If no longer “literary” then my novel, I thought, inevitably lacked the prestige that the genre inferred.

Pondering whether or not I had indeed contracted literary snobbery I sought to clearly define what was meant by the word “literary.”

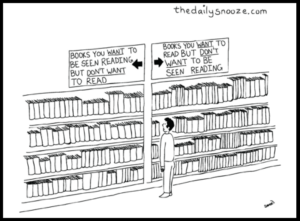

My reaction suggested that I had unwittingly developed a severe case of literary snobbery. A phrase that came to me eight years earlier when studying a degree in English Literature and Creative Writing. Back then my reading was varied and my assumption was that anyone who loved literature would expose themselves to a wide range of genres. As if intentionally setting out to disprove this theory, my then Creative Writing tutor responded to my enthusiasm for Stephen King’s earlier works by stating that he had never read a Stephen King novel. Oblivious to his slightly pompous tone, I exclaimed, “Really? Well you should give Misery a try. It’s brilliant!” He smiled thinly and commented that he couldn’t envisage himself ever reading Stephen King. In the first instance, the insinuation that King’s work represented commercial, un-literary clap trap was totally lost on me and I reasoned that my tutor simply had an extensive reading list that did not feature King. It wasn’t long before I realised that he had in fact decided that he only had time for real, good, serious, well-regarded literature. I was appalled that my tutor had formed an opinion on books he had never read, based solely on preconceived notions of genres reflecting “good” or “bad” literature.” Not that I was suggesting that someone who had never read King was missing out on anything, as taste and preference are often key factors in guiding a person towards a particular author or novel. My indignation related to my tutor’s willingness to dismiss a whole genre, thereby denying himself the possible pleasures to be derived from such lowly commercial offerings. Pondering whether or not I had indeed contracted literary snobbery I sought to clearly define what was meant by the word “literary.” Goodreads.com describes literary fiction as “principally used to distinguish “serious fiction” which is a work that claims to hold literary merit, in comparison from genre fiction and popular fiction.” In an article featured in the Huffington Post, entitled ‘Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction‘, author Steven Petite echoed similar sentiments, stating that, “Literary Fiction is comprised of the heart and soul of a writer’s being, and is experienced as an emotional journey through the symphony of words, leading to a stronger grasp of the universe and of ourselves.”

With the above in mind I decided that my tutor was justified, not in his decision to avoid commercial novels like the plague, but by highlighting the defining elements that separate the genres. After all, who could deny the literary merit of novels such as Alice Walker’s The Colour Purple, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, Sarah Waters’ Fingersmith, Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea, Rani Manicka’s Rice Mother, and of course all the Brontë, Dickens and Victorian classics, to name but a few. For me, the above titles transcend time, place and to an extent culture, by exploring universal themes. They also invariably present the reader with an emotional and intellectual challenge. Certain now that I had a sound understanding of what the word literary meant, I searched the internet for novels that others considered literary and discovered that none of the books that I rated so highly featured on any of the lists. Ironically, the majority of titles favoured were ones that I’d either never heard of or immediately decided ‘were not my thing.’ It would seem then that no matter how hard I tried to accurately define literary fiction as a genre, in doing so, I continuously reverted back to what could only be described as a matter of opinion, seasoned with notions of literary superiority.

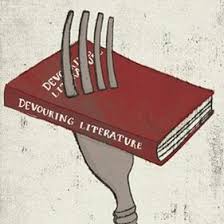

This ignited memories of a piece that I wrote for my end of year A Level English Language project. Ever an adoring fan, my then tutor the lovely Mrs Ball allocated the short story a grade ‘A’, describing it as an excellent example of original and compelling fiction. The person charged with marking the piece saw things differently and allocated it a Grade ‘C’, stating that whilst she could see what I was “attempting to achieve,” I had missed the mark by being too clever for my own good. Outraged, Mrs Ball insisted that I re-submit the piece and, low and behold a different marker agreed with her and it was allocated a final grade A. There you go, literature then is like food, with deliciousness solely dependent on the palate of the person tasting it. Of course, as is the case with most things, tastes often change over the course of a lifetime. If considering my own literary predilections, whereas during my early twenties I liked nothing better than to sink my teeth into a classic straight out of the literary canon, with The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins more than satisfying my appetite for murder and intrigue, years later I found myself devouring tasty offerings served up by Oprah’s book club, most of which included contemporary US bestsellers such as Songs in Ordinary Times by Mary McGarry Morris, White Oleander by Janet Fitch and more recently Ruby by Cynthia Bond. These days my choice of reading matter is often entirely random, so that within a three month period I may blend The Vegetarian by Han Kang with The Book of Night Women by Jamaican-born author Marlon James, finally stirring in a smidgen of retro fun by way of Nick Hornby’s About the Boy. No doubt my literary and gastronomic tastes are similar, in that I will try almost anything. My only criteria being that the narrative plot should not place undue strain on my credulity, as whilst I am more than willing to follow Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s advice by fostering a willingness to suspend disbelief for the moment, there are limits.

…literature then is like food, with deliciousness solely dependent on the palate of the person tasting it.

We return then to the initial premise, in that if we reject the notion that the words “literary” and “serious” are mutually exclusive, we may begin to see the wisdom in the contention that literary fiction is dead. Not due to a drop-in writing standards, or the failure of the contemporary, genre affiliated author to produce serious works, but rather from a decrease in the approbation of literary snobbery. If the word literary is not inherently universal but almost entirely subjective then surely this undermines the prestige attributed to literary works. Snobbery in this way becomes the act of using undefinable, culturally skewed conventions as a means of elevating certain novels to classic status, whilst dismissing others as popularist or commercial.

Why is it then that I remain adamant that the novel that I am currently working on is distinctly literary in nature? Hmmm, it could be that the shackles that bind the struggling artist to delusions of grandeur are not so easily broken. On the other hand, if we are to preserve the very best literature for generations to come then one may argue that a certain hierarchy is both desirable and essential. Would Charles Dicken’s Hard Times or Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights have survived without a literary canon that foresaw the eternal impression that such works would have on generations to come? Perhaps then it is not a question of predicting an end to serious writing but rather seeking to understanding and redefine what is considered literary in contemporary terms, with an acceptance of how the word in its original form may encompass an element of elitism that does not always stand up to scrutiny. Doing so may then provide interrogative minds with the opportunity to more clearly discern threats posed to serious fiction by agents who it has been suggested tend to favour a manuscript they deem saleable over and above a ground breaking literary masterpiece.

One Response

I wonder if you could put it in an, admittedly very rough, formula: genre fiction tolerates language in order to reach story; literary fiction tolerates story in order to play with language. Literary fiction says: this language we have is obscuring the real, we need to twist and shake it to get a clearer view; genre fiction says: this language we have is just fine. It already gives us the real. Let’s just have fun making up stories. I’d hate to be without either.