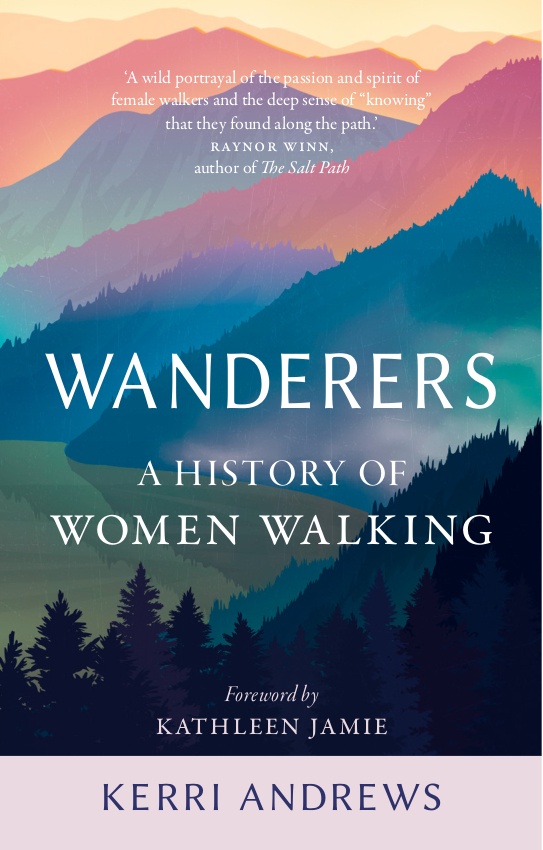

Writing my non-fiction book did not come easily. What started it all was reading Robert Macfarlane’s book The Old Ways. I read it in mid-2014, and wrote about it shortly after in my notebook, observing that most of his ‘examples are male’ – and asked the rhetorical question ‘what relationship, then, between women and paths?’ I didn’t know it then, but that was my idea. That was the idea.

The first several pages of the first notebook for this project are covered in questions, many of them indicative of my own profound ignorance of why, or how, women walked in the past. It’s not a surprise I knew nothing of women’s walking – who was bothering to discuss it? But it’s only at item six on my first list of research needs that I note ‘Read women’s accounts of walking, if they exist’. It was only after a friend told me that this was what no one else had done, that writing Wanderers really began.

Even with a clearer idea of what it was I was about, it took years for me to gather the materials. The early notebook containing my first queries was a blue RNLI book I picked up in Sennen Cove in Cornwall on a walking holiday along the South West Coast Path. It was nothing special really, just the closest book to hand. It became very important to me, though, as a space to write out my questions, my uncertainties, as well as the only place I stored the notes I made from my reading. My writing process involves making notes longhand at the same time as I read, and the quotations from my reading are interspersed with queries, as well as the beginnings of my own written response to them. If I’m lucky, when I come back to those notes I’m able to copy a section directly into the book’s draft.

The blue notebook filled up quickly, and was replaced by three others – of increasing size – before Wanderers was finished. In that first book I covered the reading for not even one chapter.

Whatever my current notebook was I found myself perpetually anxious about its location. After all, I had no backup for all the work it contained. I confess myself more careless about the earlier books, though, and a house move in the middle of writing very nearly derailed things when later I found myself needing to go back to my earliest work. It took some time before I spotted the blue cover tucked behind another layer of books on a random shelf.

The notebooks themselves are indicative of a cumulative, iterative, writing process; Wanderers took years to grow into its full form. I worked on a chapter at a time, doing weeks of research and notetaking on a particular woman and her writing before sitting down with my notebook(s) and attempting to turn that material into something more cohesive. My first few chapter drafts were very dry. Although I knew early that I wanted to write something for a general readership rather than other academics, I did not know how to do it. Working out how to tell a good story, and being able to see what made a good story, took me a long time to learn.

After four years of work I had eight chapters, and a much-improved eye for narrative. At this point I started to think about sending the book out. I knew that my chances of finding a publisher would be improved if I had an agent, so I worked up my materials and began emailing agents whose lists suggested my writing might be of interest. My excitement at reaching this stage soon evaporated, though, as my proposal was met with silence, or at best a polite ‘no thanks’, from agent after agent. There was a bright moment when one agent told me they loved the book, but that vanished when they told me they were also saying no because they didn’t think they could sell it. A few publishers to whom I’d submitted also said no, and I began at this point to seriously doubt that my book would ever be of interest to anyone.

For a while I thought about retooling the book for an academic readership, but the thought of pulling out all the story-telling, which I’d come to think of as the heart of the book, was upsetting. Almost as a last hope I sent the manuscript to the TLC to see if there was any point at all in pursuing the project further. The feedback I received was supportive and shrewd, offering technical pointers alongside tips on how to get the book published. With renewed hope I returned to drafting the book.

In the end, Wanderers found a home by luck after an article based on one of the chapters – that I placed in a popular history magazine – was seen by a commissioning editor who wrote to me and asked if I was looking for a publisher. Eight months later (after a series of further drafts) I finally had a book contract. Eighteen months after this, and the book is real, and out in the world.

I’m about to start work on a follow-up book, but I do not know if the process will be any easier this time around. I still don’t have an agent, and although Wanderers is selling well I don’t know if it’ll be enough for someone to look at my next proposal and decide to take me on. It’s comforting, though, to have a brand new notebook on my desk, waiting to be filled. Somewhere in all the notes I make there might be an idea worth reading about.

One Response

This is both inspiring and encouraging. Your account of your journey towards fruition of your idea echoes much of my own – except that I don’t yet have an agent let alone a publisher! I submitted my draft m/s (narrative non-fiction) to TLC and like you had such encouraging and, in your words, shrewd feedback from my reader, with pointers for achievable improvements.