Part 1: The Entombment of the North Surrey Gigantopithecus

Death, Rebirth, Resurrection:

In January 2018, all the cool kids sat in stunned silence and wept into their berets when, on this very blog I announced – grief and emotion adding palpable shake to my intense, kinetic and showoffy prose style – that I had abandoned my novel The North Surrey Gigantopithecus. It did not chime with the delicate sensibilities of the new mass. It was dead now, no more than wasted time trapped in a Word file forever. It had become yet more regret and shame to shovel onto my regret and shame slagheap. It was mental illness incarnate, my madness and my doom.

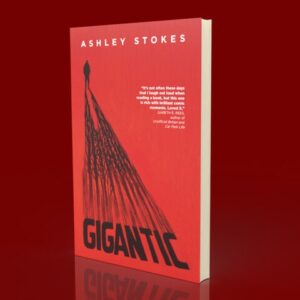

In September 2021, retitled Gigantic (I wonder why?), the novel was published by Unsung Stories. So far, the reaction has been surprisingly positive. ‘Highly recommended’; ‘the biggest thing to hit the south-east of England since that bright light that took the Planet People’; ‘rich with brilliant comic moments’; ‘unlike anything I’ve read before’; ‘a brilliant-tragi-comedy of obsession’; ‘deserves all the shining glory it can get’, ‘a sublime piece of work’. There has been a suggestion that the story would make for a Simon Pegg film a la Shaun of the Dead. Comparisons have been drawn to Garth Marenghi’s Dark Place (I know, I know, I know I look like Garth Marenghi, I am author, dream weaver, visionary). The book was part of a highly enjoyable and well-attended launch at Fantasy Con in Birmingham.

This has come as a great shock to someone who has written fiction pretty much every day since the summer of 1995 and whose published stuff usually fits into the ‘easy to admire, difficult to like’ bracket, or appeals mainly to other writers (‘How did you do that, Ash?’ ‘Don’t know!’). How on earth did I get from rejecting the novel as not the sort of thing people want to read to finding a publisher and then discovering that people do, after all, want to read a novel about Bigfoot hunters in northern Surrey formatted experimentally and written through largely the media of shouting and references to late70s-early 80s paranormal exotica and Marillion?

The first glimpse of Gigantic (aka The North Surrey Gigantopithecus) appeared to me in 2011, which provides a neat 10-year compositional timeframe (there’s more background to the actual story in this essay I wrote for the Gingernuts of Horror website). By 2016, I had written six drafts and considered it tentatively finished. Sometime in 2017, I gave up on it.

I did love the book. The decision to abandon it crushed me in a way that I could not articulate and now seems more of an emotional crisis for me looking back than I’d realised at the time.

I took this decision on advice.

I have no doubt that the advice was well-meant and sincere.

The reasoning behind the decision to abandon the book I set out with uncustomary rhetorical bombast in the original Art of Letting Go piece, but the gist the novel’s shouty, English-Lang mangling narrator, Kevin Stubbs, could align with Trump Deplorables, Brexidiots, Kipzis, alt-right trolls, libertarian psychopaths, incels and conspiracy bellends who haunt the internet and make the lives of people, especially women, hard or fearful. I didn’t want to be seen to be making light of these people or revelling in their exploits (despite the arc and outcome of the story). I may have been prey to the fervid atmosphere at the time, had allowed the infiltration of everyday life by the cheap, trashy discourse of the far right to influence my choices (the Shambler from Sutton, the Lie-Dream of the Old Ones had broken free and wanted me again, but I would be strong, I would keep running), but ultimately, I accepted that the story could be misinterpreted. In writing about Kevin, a man who believes in things that are clearly not true and makes it up as he goes along, I had created the embodiment of the Slob-Populism that everyone I know and like had suffered enough. People had already heard too much from Kev from Sutton and his mates. Kev from Sutton and his mates were shouting on Facebook that Remainers should be shot when people had already been shot.

The advice I took was good advice.

It was also the wrong advice.

If it were the right advice, I would have flushed the book and forgotten it.

Pigs will eat your face:

Abandoning it did create a sort of firebreak and I did move on to other projects. Writing about a gigantopithecus instead of the suburban Nazis and artist manqués of The Syllabus of Errors, my previous book, opened a great deal of new imaginative space for me. The failed comic horror novel made me think I should write real horror stories. A pivot towards genre fiction and literary horror has felt so far like a homecoming and a return to what originally made me love storytelling in the first place: the fantastic, the strange, the weird and eerie. I’ve even managed to deploy the sort of experimental devices I swear off in The Art of Letting Go, my story Fade to Black in This is not a Horror Story (Night Terror Novels, October 2021) using a short-film script as a spine that is annotated with footnotes and has subreddits in the footnotes).

This all came from writing about Kevin Stubbs and the late70s/early 80s SF subcultures that had inspired him and, I came to realise, had made me, too. All those references in Gigantic to Arthur C Clarke’s Mysterious World, Doctor Who, 2000AD, Omni etc now strike a chord with certain readers, and not just men of a certain edge with certain beards. I realise now that the book is not just about ‘what if there were bigfoot hunters in Sutton?’, but also what if all that counter-cultural exotica were true, is the real world after all?

The thing is, the novel isn’t about Brexit and our slide into cultural, social and political degeneracy (The Syllabus of Errors, in which north Surrey is reimagined as a Third Reich protectorate separated by geographical and temporal accident is about our slide into cultural, social and political degeneracy, FACT). The Gigantic story was conceived in 2011, when our current national embarrassment was, quite frankly, inconceivable. It was supposed to be about bigfoot hunting in Sutton. That was the baseline idea, the spark.

The shouting started when I started to compose. Ultimately, it was the shouting (shouting the odds, the shouting down, the in-yer-face shouting about the existence of a yeti in northern Surrey, the volume of it, the spite) that was at the root of the problem. In 2011, the shouting was supposed to be a warning: don’t listen to these people. Don’t be like Kev. Kev is a dangerous fantasist and twat. If you fill your ears with pigswill, pigs will eat your face.

Voice, voice, voice:

The shouting was also the key component to the voice. With its intimations of an unbottleable individual style, its combination of vision and verve, cadence and crackle, voice has always been for me the crucial element in fiction-writing. You need to be able to tell a story, yes, but you also need your own voice.

Over the years I have absorbed and been influenced by the voices of many writers, many of whom I don’t really care what they are writing about, my reaction more akin to when I listen to music or stand-up comedy. These include Martin Amis, JG Ballard, F Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Shirley Jackson, John Keats, HP Lovecraft, Vladimir Nabokov, The Roths: Philip and Joseph, Will Self, Muriel Spark, Kurt Vonnegut and Richard Yates.

My key concern, especially given the simple story arc of the nascent gigantopithecus novel, was in honing the most distinct and ornate voice possible, one capable of switching from the sublime to the ridiculous, comically mangle standard English, coin new words and phrases and mash up slang with scientific terms, all in the sort of south London accent that only has two tones: mawkishly sentimental and snarkily hostile. I was always drawn to Mark E Smith of The Fall’s way of combining all sorts of registers in a lyric, from arcane Lovecraftian tract-text to imagist-like poetry to pub slang to brutal put-downs and slag-offs. I had also liked the plaintive bark of Dave the ranting cab driver in Will Self’s The Book of Dave. I wanted to claim a bit of this for the lost boys of north Surrey, the boys from the edge of reason, boys on the brink of everyday madness, believers but believers in what?

It was all about voice and I found voice, yes, I did.

It was easy, as easy as being struck by lightning.

I don’t know whether it is true that millennial writers have abandoned voice in favour of posture and boilerplate , but it’s too late in the day for me to ditch rhythm and pulse and individuality to sound like someone who learned how to write out of a style guide to impress people with no negative capability, who trust the teller, not the tale, and only want to see themselves and their mimsy appropriations and hairshirt apologetics staring back at them from the pages of a novel or short. People are complicated and difficult. Art should be complicated and difficult. I am complicated and difficult. My book is complicated and difficult. Who is telling you the complicated and difficult truth?

Anyway, this is a longwinded way of saying the book had a high-strung vocal style and that for me was its original point: it was a novel about shouting. I wanted to sound like no one else at a time when there is perhaps a sense that all prose-fiction (at least a lot I hear at readings) is starting to sound the same (and say the same thing, pose the same pose). By chance (Twitter), I noticed that an author I knew from other projects was running an imprint dedicated totally to stories that play with the literary voice so I sent him a gigantopithecus.