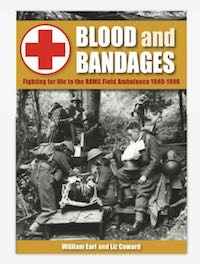

In April 2017, my first book, Blood and Bandages, fighting for life in the RAMC Field Ambulance 1940-1946 was launched by Sabrestorm Publishing. It tells the story of William Earl, a 102-year-old World War Two veteran, who served as a nursing orderly in the Royal Army Medical Corps and saw action in North Africa and Italy. As the author of Blood and Bandages, my role was to set William’s story in context so that the reader could understand and engage with his unique tale.

Unfortunately, when I started I had little knowledge of my subject but was confident that any gaps would be filled by reading War Diaries and military histories by authors such as Antony Beevor, Matthew Parker and Douglas Orgill.

I spent over five years researching the context. I interviewed William; pored over the War Diaries of the 214th and 167th Field Ambulances and the 56th London Division; I watched documentaries; studied photographs and letters; scoured the internet and devoured books. Not once did it occur to me that the focus of my book, the memories of a nursing orderly, could be crushed to death under the weight of all this research.

I spent over five years researching the context. I interviewed William; pored over the War Diaries of the 214th and 167th Field Ambulances and the 56th London Division; I watched documentaries; studied photographs and letters; scoured the internet and devoured books. Not once did it occur to me that the focus of my book, the memories of a nursing orderly, could be crushed to death under the weight of all this research.

I have learnt that this is the inherent danger of research. It can be so absorbing that its function is forgotten.

I have learnt that this is the inherent danger of research. It can be so absorbing that its function is forgotten. You can get caught up in the endless quest for knowledge until your project runs out of time or you run out energy. If you are lucky, before you have reached that point you will have had an epiphany and realised that the research is driving you away from and not towards your goal. Handling primary sources can create another unexpected danger, an intimate connection between you and the material. This is particularly so with written sources as you can begin to feel that you know the writer because you spend so much time reading their words. In fact, you can get so attached to their prose that you feel an obligation to share them with a broader readership. Indeed, I still regret that I could not include an Intelligence Officer’s humours complaint about his ‘secret’ HQ being besieged by so many Italians informers that the crowds resembled those gathering for an FA Cup Final. Most worrying of all, is that too much research can change a book’s focus because you can convince yourself that every fact is relevant, compelling and has to be included. If that urge goes unchecked, it can fatally compromise the book’s purpose. I was well on the way to doing this, when it was gently pointed out that each draft I wrote was moving further and further away from Williams’ story. I was horrified and responded by stripping the context so far back that the memoir lacked clarity and impact. It was at that point that I approached The Literary Consultancy for a professional manuscript assessment.

The subsequent report from Karl French was positive and practical. Amongst other things, he advised that I needed more context but that the additional context should be fuller and more vivid. He advised on how this could be achieved and I returned to the drawing board.

The subsequent report from Karl French was positive and practical. Amongst other things, he advised that I needed more context but that the additional context should be fuller and more vivid. He advised on how this could be achieved and I returned to the drawing board.

I asked myself, what does the reader need to know at this point, what do I want him to see and what do I want him to feel.

My starting point was William’s story. I went through each fact and asked myself, what does the reader need to know at this point, what do I want him to see and what do I want him to feel. For instance, William’s infantry division, 56th London Division, arrived at Anzio at the height of the German offensive to obliterate the Allied invasion force. The Anzio chapter is the climax of William’s military career and a key emotional turning point. William mentions Anzio obliquely in the preceding chapter, “they said that we were to join an invasion force further up the coast.” I wanted to foreshadow the horror of Anzio, so followed William’s comment with, ‘In fact, they were heading to the terror that was unfolding on the Anzio beachhead.’ That context was used purely to elicit an emotion because it was important that the reader was emotionally, not just intellectually, engaged with this chapter. I needed the reader to feel what William felt so he could empathise with William when he subsequently goes off the rails. That line of context also created pace and curiosity which justified including the background to the Anzio landings prior to the arrival of the 56th London Division. That background had to be as concise as possible to maintain the pace of the drama. When I was considering the balance between context and story at this point, I had to provide just enough context to tell a reader what they should feel and why.

Transferring that idea to the research stage. One key purpose of research in a war memoir is to explain why each memory is important or touching. Therefore, keeping the story at the forefront at all times can automatically impose boundaries which can help reduce the risk of being distracted by fascinating but irrelevant research.

Another way of trying to maintain the right balance between context and story is to count the number of paragraphs or pages between each memory. Only in exceptional circumstances should there be pages and pages of context. If it’s unavoidable, just a sentence or so from the story can be inserted to break it up. In the introduction to Blood and Bandages, for instance, I had to explain the organisation and operation of a Field Ambulance. I inserted William’s comments at the beginning and end of that section so that the reader was reminded that William was the book’s focus.

In short, it’s much easier to strike the right balance between context and story in a war memoir if you constantly refer to the story. If you focus on the research so you can write the context, there is a danger that the balance will tip in favour of context and the focus of the book will be lost.

Buy Blood and Bandages: Fighting for Life in the RAMC Field Ambulance

Direct from the publisher here

From Amazon here

From Waterstones here

You can also read more about the author and her writing processes by following along with Liz’s blog, Life’s a (Shoreham) beach

4 responses

great.

a great way to lead writing a book

thanks lilly