During my time as an assistant editor at a commercial publisher, we would receive many family history memoir submissions from people who’d inherited wartime stories about their grandparents or great-grandparents and were told by friends or family that they ‘should write a book about it!’ The sobering truth is that the audience for such specific family histories tend to be limited to those with some kind of connection to the family – which, in most cases, will mostly be members of that family, and family friends at a stretch. There’s nothing wrong with this, but invariably, writers will send in these books wondering about their chances at commercial success.

Family histories may be fascinating to some, but there’s also a good reason why they tend to be relayed piece-meal in the form of anecdotes told over the dinner table, or during family gatherings. Much like the family trees they describe, such histories are spread out over different branches and don’t typically form around a central narrative thrust that is of equal interest to everyone. Someone’s family history is interesting to them inasmuch as it tells them how they came to be: for a cousin or an aunt or a distant relative, the salient aspect is how the family tree leads to them.

For me, this problem with family histories pitched as commercial projects encapsulates quite well why thinking carefully about your audience is crucial for any aspiring non-fiction author. The question that will sway a non-fiction commissioning editor over whether to acquire your book is simple: who is going to buy it? It’s the presence – and scale – of this potential audience that determines what becomes published non-fiction, and what doesn’t.

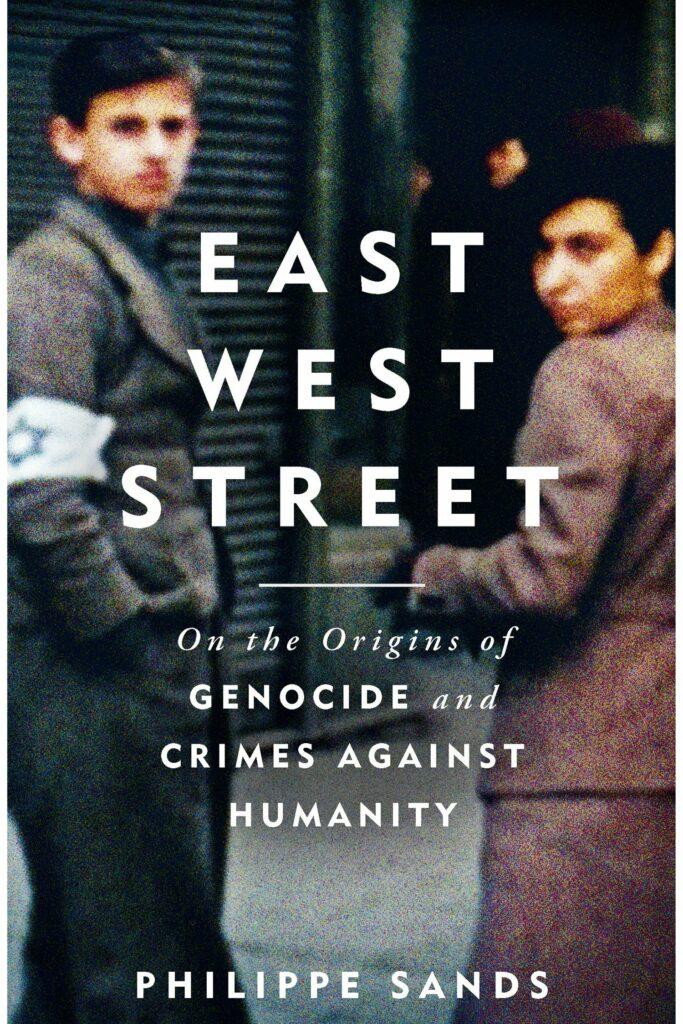

Reading, after all, is an investment of time and energy. The aspiring non-fiction author’s mission is to make this investment worthwhile. This is why Philippe Sands’ East West Street – ostensibly a family history – made an impact: not only did it describe wartime life in Lviv, a city that an English-speaking audience knew little about, it told a family story that had a powerful and moving connection to subjects of wider interest (the Nuremberg trials, and the eventual establishment of international humanitarian law). Sands’ own perspective as an expert in international law added an invaluable angle to the book, and took it beyond purely family history. The reader steps away with a deeper understanding of the profound personal tragedy of war and genocide, and the importance of international humanitarian law.

None of this is to say that writing a family history isn’t itself a valuable project, of course: it simply means that in most cases, the likelihood of such a book attracting commercial interest is low, and in many cases might be better done without the pressure of submission.

On a purely writing craft level, it can also be the case that not thinking about your audience can result in underlying issues that emerge in the quality of the writing. Wandering from one autobiographical episode to another; the prose shifts unpredictably between narrative and expository; data, anecdotes and quotations are introduced one after the other, but with no explanation given for how they fit together. In many of these submissions, the superficial inconsistencies are often a sign that the author hasn’t thought carefully about who they’re writing for.

There are three key questions to think about when it comes to your book’s potential audience:

- Who would I like to read this book? It might be a specific demographic (‘educated millennials who live in the UK’), or people with particular backgrounds or interests (‘true-crime readers looking for something different’, ‘well-informed readers who like history and romance novels’). Another way to determine your audience is to think about a particular problem someone might be trying to solve, e.g. ‘readers who want to be smarter about their personal finances’, or ‘avid gardeners who want to learn more about their hobby’.

- Why should a reader pick my book, instead of someone else’s? Naturally every reader will have their own reasons for picking a book, which are not always coldly intellectual and often dependent on instinctive reactions. However, having some idea of what makes your book yours, and not someone else’s, will help you focus your time and energy on the things that matter: do you provide a unique perspective that no one else can offer? Are you able to reach an audience that few others can? Do you have some specialist insights that you might be best placed to talk about?

- What are the one or two things I would like a reader to take away from my book? This could be an explicit take-away (‘I want the reader to understand the latest scientific discoveries about dinosaurs’) or a more implicit message (‘I want the reader to get a glimpse of what life is like as a gay man in today’s world’).

Thinking carefully about these questions not only helps you pitch a better project, but benefits the writing process itself: clarifying what kind of demographic you’re writing for helps you decide what kind of voice or vocabulary to use, for example, while knowing what is special about you or your book helps you hone in on the things that will leave the best impression on your reader. Having a message or intention in mind means that you write with a purpose, which not only helps the reader, but also fuels your motivation while you’re writing. And perhaps that’s one of the most valuable things about knowing your audience: having something to say is just as important as knowing who you’re saying it to!

One Response

Ian,

Working on a third re-write of my P. Memoirs, struggling from original material, told through four limited books, with pilot one getting ready within a month’s time from now, but for suitable publisher.

From how to like a girl, love a woman, etc.