As a writer with an attention span smaller than a fruit fly’s (despite the recent invidious comparisons with Donald Trump) I need strong stuff to keep me going – cups of fair-trade Rwandan coffee, plus a big bowl of fun-size confectionary to boost the sugar levels. However, the strongest incentive to keep writing is what Stephen King calls the “gotta”: the propulsive readable quality of genre fiction which is driven by a similarly propulsive urge to write and carry a project through. What else can return you to your wordcount other than a need to know, a Scheherazade quality that means your life depends on the unveiling of the next chapter. Genre offers both adrenalin and ready-made scaffolding, the constraints can be both liberating and rather like the straitjacket your protagonist is struggling to escape from. For a writer with concentration issues genre can be therapeutic. However, what writers fail to stress is where the real writing takes place. The gaps and holes in your synopsis are not places of pain and despair but laybys providing plenty of authorial wiggle room where you can play about with unforeseen complications.

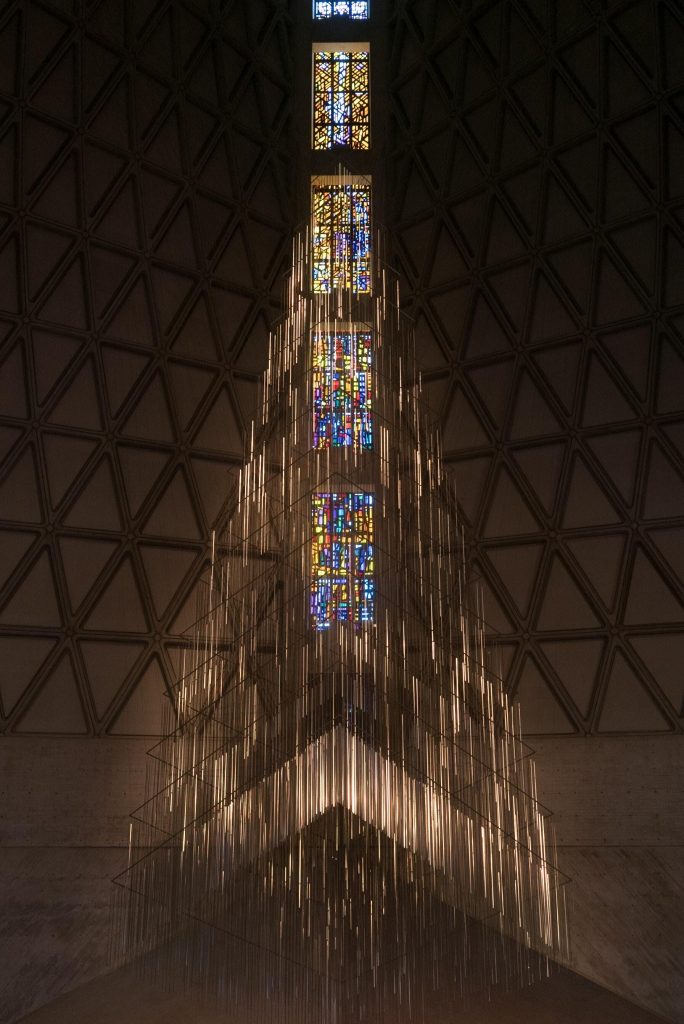

Life is frequently led on the side-lines, in the motorway service station where you might meet your future partner in the queue for something sweet. It is in the inbetweenness of places that ideas occur. Genre allows you to investigate anything you want and that happens between the rivets in the scaffolding. Imagine a hitman is hired to terminate his target on the fifteenth floor of a busy New York hotel. The hitman arrives a couple of hours early and decides not to mill about in the foyer chewing gum and leafing through magazines, generally drawing attention to himself. He thinks a little about his target the mysterious Mr Green, and then wanders through the rainy streets (naturally with his hat down and collar turned up). But in the break from killing he stumbles across a toy shop and sees the most delightful medieval castle, with battlements and waxed pennants permanently ruffled by imaginary breezes, knights with embroidered fleur-de-lys vests, Princesses and siege engines, a tall turret with a stained glass window made of actual coloured glass. The killer needs to buy it for the estranged son he hasn’t seen for six years. The killer was once a father, not always a killer — already a space in the fiction is opening up.

The castle costs $600, he will be paid $20,000 for killing a stranger (top criminologist Professor David Wilson put the price of a hit at £15,000). This castle represents all the guilt and love he feels for a son he hasn’t seen since his first birthday and it is cheap at the price. The castle represents the magic and impossibility of estrangement and childhood, a showy off gift that can fantastically heal everything, the long and important years of not being around.

Here in this aside we step out of our genre expectations and listen in to the beating heart of the story: a killer’s love for his absent son. Character, motivation and backstory are all revealed in a dramatic off the cuff purchase that was never planned in any synopsis. And now the unplanned becomes key to character and plot development.

Of course, the killer will have the castle gift-wrapped as gaudily as possible, yes to the light reflecting silver paper and the ostentatious red bow. Only then after tucking his purchase under his arm does he remember his job; only then does he realise he has fallen far short of the professional standards contract killing requires. But he doesn’t mind. The gift of love and guilt trumps everything and is key to healing the rifts in the killer’s character, intriguing possibilities arise: a contract killer who can no longer kill. A contract killer who gives his targets presents and while they’re absorbed in the unwrapping he squeezes the trigger.

The reader will now be rooting for the killer, his expanded inner life and enriched emotional responses and the dramatic question of how he will keep a low profile. Our killer returns to the hotel, avoids the lobby still clutching his package under his arm. Ten minutes to go to killing the target he is now forced to take the stairs, fifteen flights of damp stone steps to avoid scrutiny, fifteen flights carrying a castle under his arm, a castle that is much heavier than he thought and he is out of shape, too many pastries, a little asthmatic in the winter weather and when he arrives and walks the beige carpeted corridor he has to find a place to stash his present. But this refusal to relinquish the gift is also a departure from genre, a new and unexpected development that feeds directly into the “gotta.” The writing is invigorated when it touches something simple and real. Give yourself permission to wander, let the killer take time out for some window shopping and in the quiet unexpected places the story can suddenly surprise you and take hold.