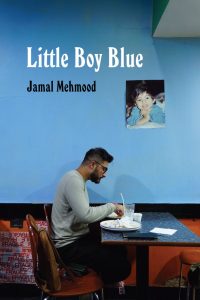

We’ve been lucky enough to have writer, poet and Associate Member of Spread the Word’s Flight 1000 scheme, JJ Bola helping out in the office recently, as part of the scheme offers three London-based aspiring publishing professionals from a background underrepresented in publishing 1000 hours over a year of training, placement and editing experience and skills development paid at London living wage. JJ, whose debut novel No Place to Call Home came out earlier this year, has been thinking a lot about the challenges of producing new work, and finding your own artistic voice. He sat down with fellow poet and writer, Jamal Mehmood (whose debut poetry collection Little Boy Blue has been published by independent press Burning Eye Books) to discuss poetry, truth, and finding your voice…

“Poetry found its way to Jamal in a number of forms, I learn, as we sit – me with a cup of green tea and carrot cake, him with a latté – and fall naturally into conversation in a rustic, central London café, as if it were part of a I haven’t seen you in ages, we should get a coffee catch up and not two poets meeting each other for the first time. The poetry came in the form of songs; romantic, and sayings; sacred, in everyday conversations, and from everyday people who would not even consider themselves poets, ‘the laymen know verses, we could only dream of writing,’ a line from Mehmood’s poem ‘Back Home I’. Poetry was a deep part of Mehmood’s Pakistani culture, his parent’s referenced it constantly, giving it a weight and significance he understood from a young age. This would help him become Poet Laureate of his secondary school and eventually the 2015 Poetry Rivals Slam Champion.

We have a shared appreciation for rap, and coincidentally, a shared favourite rapper – who we consider more writer than rapper, or at least, a tender balance of both – Yasiin Bey, formerly known as Mos Def, who, Mehmood tells me, also had a poem, ‘One Called Trill’, published in the Winter 2012 issue of the Paris Review.

“A part of finding your voice is overcoming the fear of uncertainty, the fear of doubt in your work, and your own truth.”

“But rap is hard!” Mehmood says, and we laugh at this truth as we reminisce on our failed attempts at the art. He admits that he has some music he made from his younger days stored somewhere on a hard drive, which I try to convince him to release into the world as a mixtape, or at the least, as another collection of poems. Rap was very influential in helping Mehmood find his voice. We speak of other influences from James Baldwin, who, to Mehmood, spoke with such certainty, absoluteness and understanding of his world, to his poet friend Zia (Ahmed), who, when Mehmood first listened, enlightened and astounded him with what could be done with words.

We speak about coming to terms with the poet identity, and laugh at how akin it was to a “coming out”, in that, you reveal a huge part of yourself and your experience – particularly to strict immigrant parents whose main focus is education – that only you understand. But why poetry? A question we have both wrestled with time and time again, especially in this day, in this world.

We speak about coming to terms with the poet identity, and laugh at how akin it was to a “coming out”, in that, you reveal a huge part of yourself and your experience – particularly to strict immigrant parents whose main focus is education – that only you understand. But why poetry? A question we have both wrestled with time and time again, especially in this day, in this world.

“You look like someone who has sat with themselves,” I say, which resonates with him as we fall into a momentary shared silence. There’s a sombreness about Jamal. The dust settles for him to speak about his experiences. Poetry helped him during a rough time in his life, particularly in relation to his mental health. He expounds on the depth of this experience and how much he still carries with him today, and I sit in awe, listening as if someone were telling a part of my own story back to me. Perhaps it is whatever comes to find us in our darkest moment, that light, that we call poetry. Lucky are they then who are found.

A part of finding your voice is overcoming the fear of uncertainty, the fear of doubt in your work, and your own truth. Mehmood laments how, even now, it is something he struggles with. He recently wrote an essay, which included several equivocal words, ambiguous phrases, and multiple uses of maybe, perhaps, or possibly, as a way of absolving the responsibility of being right, and the likelihood of being wrong, and his friend pulled him up on this. I found this interesting as this fear is something that is absent from his work, Little Boy Blue, Mehmood’s debut poetry collection, which is written with such certainty, such truth, such melancholy, but also such joy.

Maybe then, this is the poet’s only task, to write the truth of their world, and be less concerned about being right; that can be left to the politicians. The only task is to express a truth that comes from experience, and share that experience with others, that we may learn ourselves, and shed light to our own being. A poet’s voice, then, is not something that is found, rather, it is something that emerges. And ultimately, it’s not about what poetry does, but what it gives us; an opportunity to capture memory and turn it into form.”

One Response

I’d like to have an idea or express some kind thought but I’m too emotionally stunted to make any valuable comment.