Write-up by Jonathan Ruppin

After a week of record temperatures in London, the weather was mercifully cooler as delegates filled every seat at The Literary Consultancy’s third Writers’ Day, introduced by Director Aki Schilz.

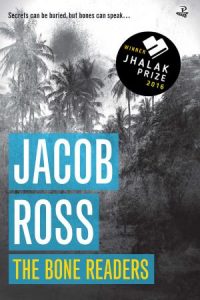

The first speaker was Jacob Ross, inaugural Jhalak Prize winner and editor at Peepal Tree Press, who gave a talk brimming with passion and ideas. His topic was plot point evolution – as a mentor to writers, he often works on the underlying structure their narratives.

He opened by pointing out that, as readers, we look for causality – we are driven by the human instinct to ask ‘why’. The field of anthropology, he told us, now focuses on the narratives that have shaped humanity, indicating that telling stories is not a trivial part of our culture.

“as readers, we look for causality – we are driven by the human instinct to ask ‘why’”

Writers have to begin with a set-up, constituting the first 20-25% of the novel, and this is what publishers examine when asking for the first three chapters or thirty pages. In a world overfull of talented writers, writing of great quality is no longer enough – a fresh approach with well-established narrative ambition is necessary. Thematic concerns also need to be apparent, but he did later warn against allowing these to smother the storytelling. The point of a fiction is to get your novel read to the end and to achieve this, readers need to perceive what’s pushing or pulling main characters, as well as developing empathy for them.

He turned to PowerPoint for a number of graphic representations of storytelling, illustrating the escalation of the plot towards its climax and warning of the dangers of ‘mid-novel sag’. He focussed on the classical four-act structure, as used by Jane Austen and in his own book The Bone Readers: set-up, confrontation – which should take up at least half of the word count and is split by a major reversal round about its midpoint – and resolution.

He turned to PowerPoint for a number of graphic representations of storytelling, illustrating the escalation of the plot towards its climax and warning of the dangers of ‘mid-novel sag’. He focussed on the classical four-act structure, as used by Jane Austen and in his own book The Bone Readers: set-up, confrontation – which should take up at least half of the word count and is split by a major reversal round about its midpoint – and resolution.

He even came up with an answer to that eternally debated question of the difference between literary and genre fiction; the former focuses on mapping the inner life of the characters; the latter on the action of the overarching plot.

You can’t bullshit readers, he concluded. Fiction must uncover the truths of what life is truly like and acknowledge what we are capable of as human beings, at our best and worst.

Max Porter, editorial director at Granta Books and author of multiple award-winning Grief is the Thing with Feathers, began first by concurring with most of what Jacob had said, before going on to suggest that writers can do anything they want, if they do it well, but you do have to understand the rules before you can try breaking them.

He said his origins in independent bookselling have informed everything he’s done in publishing – he strongly recommends that writers thoroughly research the area of the market for which they’re writing. The benefits of reading widely cannot be understated either.

He spoke of the many reasons to celebrate what the book world does, including its broader cultural and political role, but he also quoted Flannery O’Connor advising writers to choose between artistic and financial success. She also warned that writing fiction is no escape from but ‘a plunge into reality’.

“You can’t bullshit readers. Fiction must uncover the truths of what life is truly like and acknowledge what we are capable of as human beings, at our best and worst.”

After a digression into the absolute necessity of acquiring an agent, to look after every aspect of your writing life, he went through the process of acquiring a publisher, offering tips on avoiding the swinging axes that threaten all of the fifty or so submissions, three-quarters of them fiction, he receives each week.

Books that suit the list, usually from trusted agents, are next examined with a readerly eye – this is the point at which the editor needs to fall in love with a book as much as any other reader might.

Is it original? Where will it sit in the market? And, at Granta, there’s the issue of whether a big publisher is going to offer much more money – Max once lost out on a book for which he’d offered £10,000 as one of the giants had stepped in with an advance of a million.

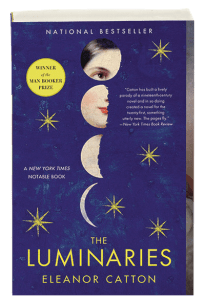

For Granta, the potential of an author is a major factor. Eleanor Catton’s debut The Rehearsal was bought as much for the book they expected she’d write further down the line much as for the book itself – she was to win the Man Booker Prize for her next, of course!

For Granta, the potential of an author is a major factor. Eleanor Catton’s debut The Rehearsal was bought as much for the book they expected she’d write further down the line much as for the book itself – she was to win the Man Booker Prize for her next, of course!

Jacob had said that a novel needs to win over a potential publisher in its first thirty pages, but for Max is figure is more like five, such is the volume of what he reads – he rarely goes further with books he rejects.

But once he’s convinced, he shares it with colleagues and they discuss the manuscript in considerable detail. He does feel that he’s earned the right to acquire less obvious titles. When he presented the team with Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, the sales department asked him to stop buying weird books – it was rejected by 14 other publishers – but it’s gone on to sell 170,000 copies. There was also scepticism about his own ‘weird’ book in certain quarters at Faber when they were considering taking it on.

Once it’s been acquired, an editor will work with the author on the architecture of the book – Max read The Luminaries nineteen times. And while the author works to finalise the manuscript, the editor is free to start work on production details and the marketing plans.

Typesetting is an aspect he finds a magical part of the process, loving what was brought to Grief is the Thing with Feathers by its layout – he does feel that readers are alive to such nuances. This led to a gripe about Amazon, whose algorithms he feels simplify readers’ habits to an absurd degree – it’s a part of why bookshops are still favoured by so many readers.

He read the scintillating opening paragraphs of two books that had won him over immediately when they were submitted – The Vegetarian and Such Small Hands by Andrés Barba, translated from Spanish by Lisa Dillner, which Portobello publish in July.

With a quick warning against being distracted by negative online reviews, he finished by encouraging writers to stay true to their own vision – anything goes so long as it’s well done.

“anything goes so long as it’s well done”

After lunch, the afternoon session began with an absorbing reading by bestselling historical fiction writer Giles Kristian from his newly published novel Wings of the Storm. He recalled how useful a TLC report had been for him back in 2005, helping him secure a deal with Transworld a year later and is now has nine books to his name.

This was followed by the eagerly awaited live pitch of the five shortlisted authors for the TLC’s Pen Factor Writing Competition. Watching over the nervous authors from the Free Word Centre’s mezzanine level were the four judges: Ed Wilson, agent at Johnson & Alcock; Crystal Mahey-Morgan, who left Random House to set up transmedia publisher OWN IT!; Emma Paterson, agent at Rogers, Coleridge and White; and Angelique Tran Van Sang, editor at Bloomsbury.

This was followed by the eagerly awaited live pitch of the five shortlisted authors for the TLC’s Pen Factor Writing Competition. Watching over the nervous authors from the Free Word Centre’s mezzanine level were the four judges: Ed Wilson, agent at Johnson & Alcock; Crystal Mahey-Morgan, who left Random House to set up transmedia publisher OWN IT!; Emma Paterson, agent at Rogers, Coleridge and White; and Angelique Tran Van Sang, editor at Bloomsbury.

(I’d been one of the readers who’d helped narrow all the delegates’ entries down to the shortlist of five and, having been delighted by the very high standard of entries, I was very keen to hear the chosen authors pitch.)

First up was Gareth Strachan, reading from his picaresque novel of friendship The Drunken Bricklayer, about two eccentric antique dealers in search of a piece of rare glass that gave him his title, a sample of which he brought along. He uses the glass they collect as a metaphor for the fragility of mental health. The judges found it full of character and energy, with great praise for the humour in the writing.

He was followed by Susan Angoy, who read from Whisper of Lies, a story of colonialism, transracial love, identity and the burden of family secrets. The judges felt the setting of Guyana was conveyed particularly vividly and the characters were full of life, and loved the poetry in her prose.

Then came Kololo Hill by Neema Shah, about a family fleeing Idi Amin’s Uganda in 1972, which explores themes of displacement, loyalty and the search for freedom. The lyricism of her writing made a strong impression on the judges, who thought it a very finely judged presentation of distressing events – it was one they wanted to read more of.

Fourth was Jeremy Gavin, reading from his moving memoir The Stonewalls of My Mind, which recalls a childhood growing up gay in a strictly Roman Catholic community and how he came terms with the false memories his mind created to cope with the conversion therapy to which he was subjected. The judges praised his bravery in writing it, suggesting readers would find it hugely affecting. It also resonates as love story, a tribute to the lover he lost.

Finally Alison McCullough read from The Noble of Art Letting Go, a novel that explores guilt and secrets from the past can hang over the present. The judges felt the feelings of claustrophobia created by the first-person narrative were evert effective, finding great intimacy in the writing and wonderful use of tiny details.

The judges conferred intensely and then Aki took the stage to announce the winner: it was Neema Shah who collected the prize package worth over £1,000.

While judges conferred, we moved on to the afternoon Finding Markets panel. This featured Jonathan White, Sales & Marketing Manager at self-publisher Troubador, who has an extensive retail background too; literary agent and marketing consultant Julia Kingsford, formerly Head of Marketing at Foyles; and Stefan Tobler, Publisher at literary press And Other Stories, who is also a translator in his own right.

The panel emphasised the importance of thinking about marketing possibilities from the earliest stages of writing a book. This is particularly true in the case of self-published works, noted Jonathan, where getting a book into shop requires building relationships with retailers.

These days, it is, whether authors like it or not, as much about them as it is their books. (This is argument against writing anonymously or under a pen name.) Julia framed this is thinking about your personal narrative as well as that of your book – promotional opportunities over revolve around telling readers specifically why you’ve chosen to write your book. These days it’s as much about the author it is the book, which is why publishing anonymously or under a pen name is rarely advisable.

“These days, it is, whether authors like it or not, as much about them as it is their books.”

To get a self-published book into a bookshop requires building relationship with local retailers – just turning up with finished copies in hand, hoping to be stocked, is unlikely to get you anywhere. Several audience questions inquired about the advantages and disadvantages of self-publishing and it became clear that any author who goes down that route needs to commit significant resources to their marketing efforts.

Julia also mentioned thinking about why stocking your book will be good for the retailer. Prime display points boost the sales of whatever is put there, so bookshops try to find which titles will benefit most from that extra exposure. It can be good, for example, to make your local connection or special knowledge in a particular field into selling points.

Julia also talked about making use of your community – mobilise your friends and family. As people who care about you, they can actually play a major part in getting word-of-mouth going – they’re sure to want to tell everyone!

“…mobilise your friends and family. As people who care about you, they can actually play a major part in getting word-of-mouth going – they’re sure to want to tell everyone!”

And Other Stories does accept unsolicited submissions (although this process is on hiatus while they move up to Sheffield), so Stefan talked about how to go about selling your book to publishers. He stressed the the importance of tailoring your approach to who you’re contacting, putting as much effort into crafting your cover letter as you do your book and engage with people on a human level. Perhaps bucking the general view of publishers, he did say he was happy to look to take on a single book from a writer, rather than necessarily expect it to be the first of several.

Julia pointed out the importance of getting other people to read your manuscript first: many submissions are several drafts too early and need revision, ideally with the help of professional advice. It should be as good as you can make it. And how your early readers react may offer hints on how best to pitch a book.

Her final caveat echoed Max’s editorial take: whatever you do will only work if the book is any good.

“whatever you do will only work if the book is any good”

Aki brought proceedings to a close with words of encouragement to every writer and thanks to everyone involved in the day. The last of these were to Becky Swift, co-founder of The Literary Consultancy, who sadly died in April. She was very much missed, but Aki and her tireless assistant Joe Sedgwick can be assured that she would have loved every minute of this year’s Writers’ Day.

Writer bio

Writer bio

Jonathan Ruppin has worked in the book trade for 22 years, including 13 years at Foyles. He has been a judge of numerous literary award, including the Costa Novel Award and the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize. Ruppin founded the English PEN Translated Literature Book Club and is a member of their Writers in Translation Committee. After a year at Literary Director as a digital publishing start-up, he is currently planning new projects.