Launching The Ruppin Agency earlier this year was a logical step for me. But it was more than just working out how best to use my experience. There are many excellent literary agents out there, so I need to be different. And that difference comes from what I’ve come to understand about not what is published, but what is not.

There are many excellent literary agents out there, so I need to be different. And that difference comes from what I’ve come to understand about not what is published, but what is not.

The book world prefers to think that we merely skim off the cream that has naturally risen to the surface. We bridle at being called gatekeepers, but while there is much life outside the walls of traditional publishing, conditions of entrance to the citadel remain largely arcane and dynastic.

Back in 1999, while I was preparing for an interview for a job as an editorial assistant, I found myself reviewing what I’d read in the previous months. I was curious to see if there were any patterns and I was shocked to realise that 48 of my previous 50 books had been written by men. I immediately decided to nothing but books by women for the next year and whenever I’ve subjected myself to an unannounced inspection since, I’ve found a balance.

But, at the time, I assumed it was just some sort of personal narrow-mindedness, probably resulting from having been to an all-boys’ school. I didn’t wonder if it was a wider phenomenon, nor did I find myself considering other ways in which I might be limiting my reading.

The debate about whether bookshops should feature black or LGB (that was as far as the acronym stretched back then) fiction sections was what started to crack open the issue for me. There’d be complaints when we didn’t have such sections, but there’d also be those unhappy when we did. What this dichotomy highlighted was that black and LGB writers were poorly represented in the literary world and, when they were acknowledged, it was as some sort of non-mainstream ‘other’.

The corollary to this is the presentation of the experience of being white as a default and universal perspective. By the time I was introduced this this concept, I was working at Foyles, a more multicultural place than most in the book trade, and I had colleagues who were starting to push ideas such as ensuring that there were authors from a wide range of backgrounds in every promotion.

It was drawing up these selections that made the scale of the issue apparent. Finding enough women, for example to include on a table of history or science books always needed extensive research. But it was always worth it, because readers – and this is something the book industry tends to forget – are both more curious and more disparate than we assume. (It’s frustrating that this still has so little mainstream traction – the Richard & Judy Book Club, for instance, has now gone 11 series without featuring a BAME author.)

Foyles was always a bit of flagship for indie bookselling, so there were networking opportunities galore. I met not just countless authors, but also their agents, editors and publicists, the people behind the sales and marketing of their books. And they knew me as someone who read widely and voraciously, who’d champion anything that could be a winner with Foyles’ customers. As well as glamorous launch parties and advance proof copies of forthcoming books, I got to judge literary prizes, to interview authors onstage and on the page, to be interviewed on radio and TV.

Foyles was always a bit of flagship for indie bookselling, so there were networking opportunities galore. I met not just countless authors, but also their agents, editors and publicists, the people behind the sales and marketing of their books. And they knew me as someone who read widely and voraciously, who’d champion anything that could be a winner with Foyles’ customers. As well as glamorous launch parties and advance proof copies of forthcoming books, I got to judge literary prizes, to interview authors onstage and on the page, to be interviewed on radio and TV.

Now, it’s always seemed a little short-sighted that publishers and agencies draw so few of their staff from bookshops. They lack that practical experience in observing customers browse the shelves and choose books.

Now, it’s always seemed a little short-sighted that publishers and agencies draw so few of their staff from bookshops. They lack that practical experience in observing customers browse the shelves and choose books.

So how about a bookseller-turned-literary-agent? I had good relationships with all the publishers I’d want to work with and, picked up through various projects, well-honed editorial instincts.

Through the authors I’d got to know, I also come to understand how many talented writers there are out there now. It’s very different from when I was an agent’s assistant, much earlier in my career. Many more people feel emboldened to write, and the burgeoning of writing courses, along with and opportunities to share feedback with others online, has boosted the general standard markedly.

It’s very different from when I was an agent’s assistant, much earlier in my career. Many more people feel emboldened to write, and the burgeoning of writing courses, along with and opportunities to share feedback with others online, has boosted the general standard markedly.

My partner, the writer Emma Claire Sweeney – without whose support, belief and wisdom The Ruppin Agency would never have been conceived – has shown me life outside the walls of publishing, through the experiences of her vast network of published and unpublished writer friends. One, for example, was told that black people don’t really read books; another has written a novel set on council estate that is loved by countless editors but none will take on. Emma herself has published a novel and a work of literary biography in the last couple of years, but only after being hearing that disabled characters, friendship between female writers and setting a novel in the north are all things unlikely to appeal to many readers.

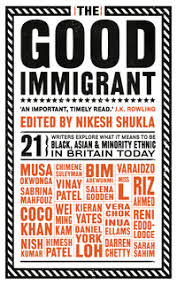

Thanks to an increasing number of passionate and inspirational people in the book trade, a shift in attitudes is gaining momentum. I doubt I’d have attempted to launch my own agency without the insight and determination of Nikesh Shukla, editor of The Good Immigrant, and Julia Kingsford, who has long campaigned on issues of diversity – their project for launch in 2018, The Good Agency, is a diversity initiative of an unprecedented ambition.

Thanks to an increasing number of passionate and inspirational people in the book trade, a shift in attitudes is gaining momentum. I doubt I’d have attempted to launch my own agency without the insight and determination of Nikesh Shukla, editor of The Good Immigrant, and Julia Kingsford, who has long campaigned on issues of diversity – their project for launch in 2018, The Good Agency, is a diversity initiative of an unprecedented ambition.

Thanks to an increasing number of passionate and inspirational people in the book trade, a shift in attitudes is gaining momentum. I doubt I’d have attempted to launch my own agency without the insight and determination of Nikesh Shukla, editor of The Good Immigrant, and Julia Kingsford, who has long campaigned on issues of diversity – their project for launch in 2018, The Good Agency, is a diversity initiative of an unprecedented ambition.

But there’s another barrier to be overcome before the book trade can face up to the imbalances of opportunity that still exist. Most people working in books will proudly assert their liberal values – so to accuse us of prejudice is an attack on our sense of identity, on who we are proud to be. But the inculcation of a perspective that sees white middle-class perspectives as the lens of literature means that unconscious bias is engrained.

This means that I could pat myself on the back for reading a book by a writer who is working class or Muslim or transgender, and then fail to register that my next ten are by people just like me. That’s the default, the go-to, the normal.

So every writer from outside whom we do allow a place at the table is there to fulfil a quota, to tick a box, to make us feel that we are doing our bit. This ‘othering’ of writers from beyond publishing’s traditional spawning grounds is part of the privilege that is very hard for us to concede.

It is painful for me to admit that I have viewed writers from backgrounds other than my own as emissaries of their culture, that I have considered an author more for the colour of her skin, for example, than for what she has written. Everything I believe I stand for tells me I am not prejudiced, yet I have acted in a way that is, by definition, prejudiced.

My background means that I have never been restricted to writing solely from my own standpoint. And neither should anyone else be. Authors should write whatever stories they are aching to tell, not justify being accredited by fulfilling some social purpose.

Authors should write whatever stories they are aching to tell, not justify being accredited by fulfilling some social purpose.

It is a deeply uncomfortable experience to come to realise that there are times that I have insensitively looked on writers as representatives; I may yet, unthinkingly, do it again. It’s a new experience too, to understand that just to be who I am isn’t enough, something I’ve been privileged to avoid until now.

This, of course, is why a greater range of backgrounds among writers is interdependent on greater diversity within the publishing workforce. It’s not simply about the numbers either: after all, there may now be more women than men working in publishing, but few of them are in decision-making echelons. There’s a worrying implication there that new perspectives coming from within the industry still aren’t actually being paid much attention. For more marginalised groups, the challenge remains vast.

But I’m trying not to be daunted by the scale of it all. If publishing changes, it will be through the contributions of very many people. I hope that, in doing my bit, I can help others join in as well.

3 Responses

Dear Jonathon,

Best of luck with your new venture, booksellers shelves everywhere, seem to groan with predictable offerings/titles.

On an entirely different note however, can I just say that one thing about your resume, struck me as absolutely preposterous, however typical of British publishing today.

Namely, the no of major prizes a non-writer like yourself has been asked to judge?

It may be a reality of the trade but I still find it absurd.

Best wishes,

MC.

Hello Mick, thank you for your comment. I would say that by this logic, editors ought to be writers too, but most of them aren’t and often the book is the better off for it. Some writers of course make great reviewers and literary critics, but the skill and expertise required is, I would posit, a very different one to being the creator of a work of fiction. Not all writers make good editors, and whilst one would hope they are all readers, they might not make the best critical readers! (The same of course might be said of film, dance, theatre…) All very best, TLC

Dear Johnathan

Glad to hear that you’re doing well with your agency. I’m an award winning poet here in the States. My prose is also very poetic. By the way, I’m a disabled Jewish woman. Would your agency be interested in someone like me? Just curious, how big is your agency?